Graphic Medicine: A Powerful Tool for Teaching Empathy

On the occasions when we visit our family physician or other caregiver, we may find ourselves feeling vulnerable or unwell. During these times, we all desire to be treated with kindness, compassion and empathy. We want to feel important, comfortable, worthy and heard.

Even if we can’t express it, we need to feel empathy from our medical professionals. Active listening, asking open-ended questions and showing validation and patience helps us to feel at ease.

Empathy can be challenging to quantify, let alone teach. Emotions are complex and may be hard to standardize if similar experiences are not shared. Cultural differences can influence how empathy is perceived. Despite the challenges, it is crucial to teach empathy in medicine to foster compassion and effective communication.

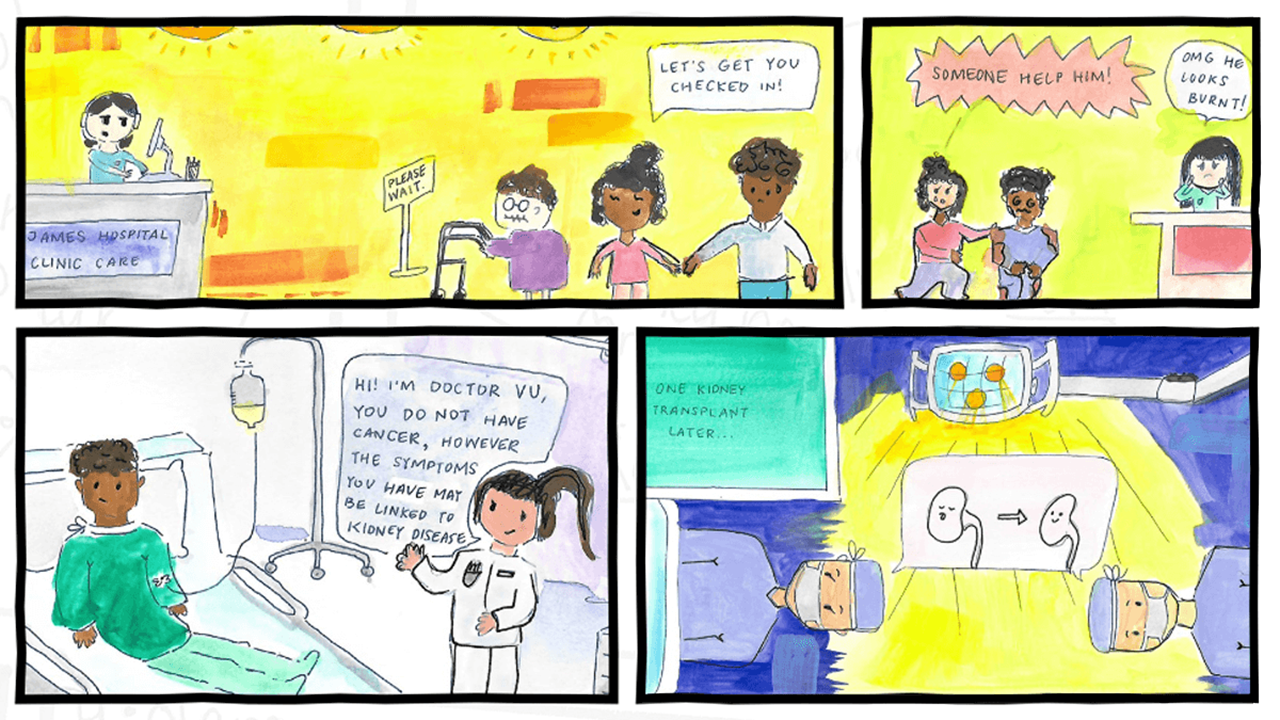

By depicting personal stories and complex medical topics through visuals, graphic medicine is a medium that helps medical students and professionals better understand and connect with their patients’ emotions and experiences. Incorporating graphic medicine into medical curricula can enhance communication skills, cultural sensitivity and compassionate care, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Anna Simonson, MLIS, Ph.D., a librarian at USD’s Wegner Health Sciences Library, discovered the medium by accident. “I kind of stumbled across the idea,” she says, “but it captured my attention as something that could be useful and fun, so I pursued it.”

Shortly after that accidental discovery, Simonson began attending graphic medicine conferences. She is now a part of the Graphic Medicine International Collective, a diverse community that includes cartoon artists, librarians, physicians, nurses and other health professionals. The core mission of the collective is to incorporate comics in health and spread kindness, compassion and inclusivity.

Graphic medicine as a concept is not new. The term “graphic medicine” was coined by British physician Ian Williams 20 years ago. Dr. Williams wrote his own graphic medicine novel, “The Bad Doctor: The Troubled Life and Times of Dr. Iwan James,” which was published in 2014. In the novel, weighed down by his responsibilities, Dr. James doubts his ability to make decisions about the lives of others when he may need more than a little help himself. The novel follows Dr. James as he takes on life’s responsibilities while grappling with his own OCD. Dr. Williams is also the founder of graphicmedicine.org.

This field of interest is constantly changing, and its practice is becoming increasingly recognized as a viable medical education tool. Medical schools such as Dartmouth and Penn State have absorbed graphic medicine in curricula, demonstrating the value of its use.

Because of its emphasis on kindness and art in medicine, it was a natural fit to bring graphic medicine into the SSOM’s Section on Ethics and Humanities, where Simonson holds an adjunct faculty appointment. Established in 1995, the section values ethical leadership and the enriching aspects of humanities education. USD prioritizes nurturing the well-rounded growth of future health care professionals and has championed an integrated exposure to a range of humanities, including art, music and literature.

Simonson and Leah Seurer, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Communication Studies at USD, have thus far offered two learning sessions for SSOM residents. During the first, the group read excerpts from “My Degeneration,” a memoir that examines one patient’s devastation and experience with the health care system after receiving a Parkinson’s diagnosis at a young age. Core themes of the text are doctor/patient communication and the wide-ranging repercussions of the disease.

Armed with crayons and paper, Simonson and Seurer asked the residents to draw one example of either good or not-so-good communication they have had or witnessed with a patient(s). This was followed up with the task of drawing the opposite: What could have made the communication better or worse? While at first, the task was intimidating, it helped many of the residents express their feelings about a difficult but core part of being a physician: delivering bad news.

“People quickly realize they don’t have to be professional artists to participate,” Simonson says. “The importance is about the idea and feeling behind the process and not how ‘good’ the art is. The process provides for both the reader and the storyteller.”

The group then compared their own drawings/ experiences with the author’s, which Simonson says assisted in helping them focus on relatable situations. “We talked about how they want their patients to perceive them as both experts and caregivers, and the difficult balance between those things, especially when they don’t have a lot of time with each patient,” said Simonson.

Although graphic medicine is not a required piece of the SSOM curriculum, Simonson does teach an undergraduate honors seminar at USD called Graphic Medicine: Improving Patient Care and Health Literacy Through Graphic Novels.

For Simonson, graphic medicine evolved from a piqued interest to a full academic, three-credit course when she answered a call for proposals for new courses for the USD’s Honors Program.

Simonson taught the course and said, “I’ve never had so much fun teaching. The students, many of whom are planning to work in medicine, had a strong interest in talking about health care in a less clinical way. We talked about everything from the history of comics to health literacy and difficult scenarios that might benefit from the inclusion of pictures.

“Many things are written at a level that is too difficult to understand, too filled with jargon,” continued Simonson. “Even discharge instructions can be too complicated. Communication is so important in health care. Research shows that miscommunication is how common errors can happen.”

Anna Myrmoe, a 2024 graduate of the SSOM and a first-year internal medicine resident, says her initial exposure to graphic medicine was during the first week of her residency when Simonson and Seurer gave a talk about the topic to residents. The duo was able to show how graphic medicine has helped medical students and residents at other universities to see each patient as a whole person.

This empathy is important, says Myrmoe. “When you sit with a patient face to face, you get their health history and personal experience of what they are going through,” she explained. “You get a very quick version of why they are in your exam room in the allotted time, usually just 15-20 minutes. All we can go on is how much they are willing to share in that time. I find these books let us see a bit deeper into what they and families go through. It’s eye opening and humbling.”

Myrmoe thought the idea of improving discussions and having honest conversations with patients was something that should be available to more residents. “It was fascinating that there are all these types of illustrative reads out there,” she said. “I thought it would be cool to try a book club.”

The group meets every three months to discuss a particular graphic medicine novel. While it originally started as a group open to internal medicine residents, it has grown to a gathering of those from all specialties. The gathering generates great conversations and facilitates meeting new people.

Thus far, the group has read and discussed three graphic novels: “Mom’s Cancer,” “Menopause,” and “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?”

Myrmoe found personal connections between her own life and the novel “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?”, which is about the protagonist’s aging parents. “In the novel, they avoided difficult discussions until the very last minute. It brought out elements of humor, sadness – all sorts of emotions.”

“It’s so raw and honest,” she continued. “You are reading initial reactions to things, not an edited or polished piece. It’s much different than a highly edited memoir of what someone is going through. It has been my favorite because of how relatable it is.”

Transforming difficult topics into learning opportunities to improve empathetic responses aligns well with the aptitudes expected of medical students across the nation.

“This initiative addresses some of the core competencies for residency established by the ACGME,” Simonson said. These include interpersonal and communication skills, as well as professionalism.

“Ultimately, I hope everything we do emphasizes kindness,” Simonson explains. “That is a core thing that graphic medicine can do – it highlights emotions in a way that text alone just cannot. It’s really about understanding each other.”

The Wegner Library collection of graphic medicine books is modest but growing: Around 40 physical books are accessible at Wegner and 20 or so in ID Weeks, Simonson said. Graphic medicine novels in e-book form are also available. Simonson hopes students and residents who are exposed to graphic medicine now utilize the practice as they move forward in their careers.

“I have a deep sense of respect and compassion for the work that physicians do, and I hope graphic medicine brings them enjoyment,” she said. “I hope it provides them an outlet to process the difficult things they see and deal with every day. I hope the act of drawing gives them a sense of relief, because drawing in and of itself is therapeutic.”

Myrmoe agrees, saying, “I will definitely use graphic medicine moving forward in my career. It’s such an unusual type of genre that it’s hard not to want to keep up with it. There are certainly enough topics and titles we’ll never run out of learning opportunities.