Justice Through Science: The Life and Logistics of a 'Last Responder'

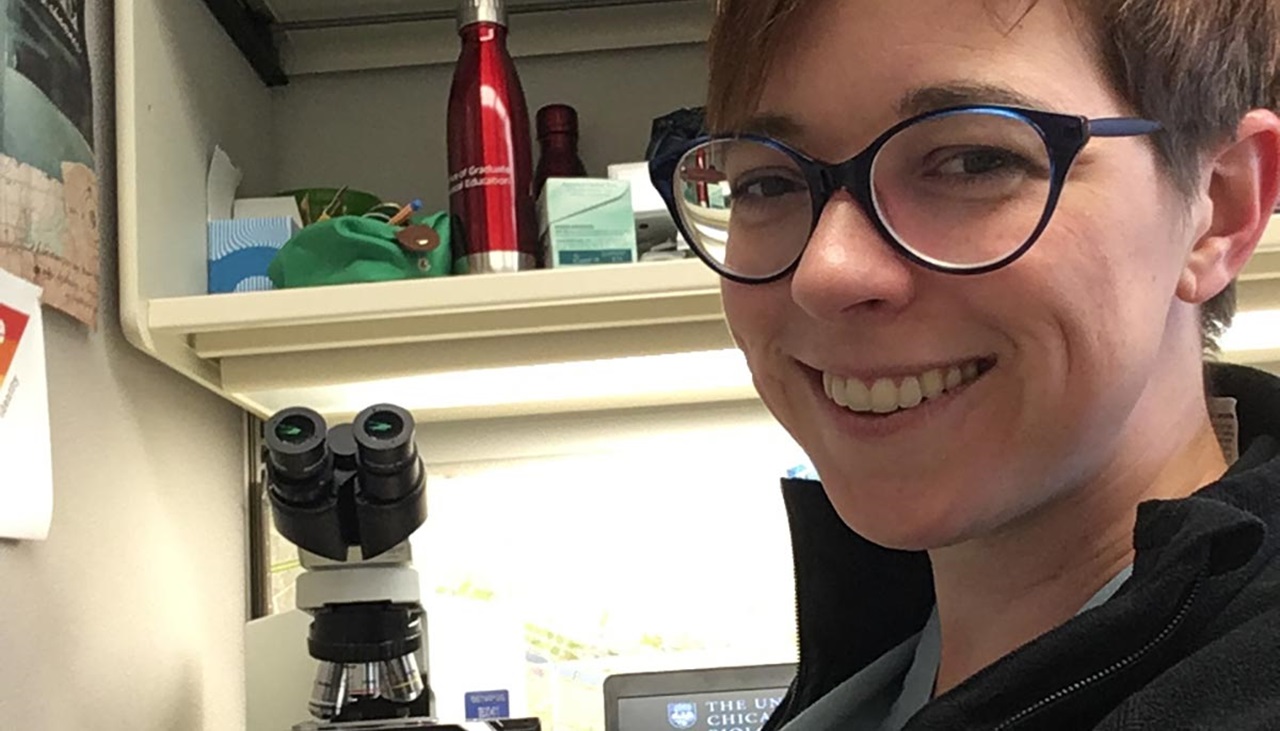

The 2016 Sanford School of Medicine graduate is a forensic pathology fellow in one of the country’s busiest offices—Cook County, Illinois, home to Chicago. The Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office has a jurisdiction of 5.2 million people, roughly 45% of the population of Illinois.

The Office of the Medical Examiner fills a vital role with public health and health care at large. One of the office’s most important duties is to the families who have lost a loved one, often suddenly and unexpectedly. Whatever the circumstances, the medical examiner’s office works with families to help them through the process, treating them all with dignity and compassion.

In 2020 in Cook County, 52,037 deaths were recorded, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health. Approximately 16,000 of those are reported to the medical examiner’s office annually and around 5,600 are accepted for further investigation. Autopsies are conducted on about half of those cases.

For Reynolds, each workday presents her with an opportunity to solve a riddle and, in many cases, bring closure and understanding to loved ones of a decedent. In a facility with 51 unclaimed and 88 unidentified cases on record within just a few months of 2022, that closure is important.

“We see a lot. It can be very sad, to bear witness to family or next of kin when everything is still very raw for them,” she stated. “But that can be said, too, of many other areas of medicine.”

The job of a medical examiner, a pathologist with subspecialty training in forensic pathology, is to uncover the truth, carefully and meticulously, of what has happened to a patient who has suffered a fatal condition. A blend of biology, anatomy and detective work, the painstaking procedures involve performing autopsies and examining organs, tissues and bodily fluids to determine abnormalities that may have resulted in death.

The medical examiner’s office Dr. Reynolds works in is independent but often interfaces with law enforcement and the judicial system. By law, the medical examiner’s office is required to investigate and certify all deaths that occur by violence, without explanation or medical attention, are related to drugs, of persons in custody or which pose a threat to the public health.

“Investigators document the death scene and what happened, and I use those reports and photos to decide what procedures I’ll need to do for each case,” Dr. Reynolds explained.

Dr. Reynolds arrives at the office before dawn on the mornings she is scheduled to work on cases and reviews her assignments for the day. “My co-fellows and I discuss our cases with our attending pathologists, and then head to the autopsy suite,” she explained. “I’ll read about my cases, see what’s known and what isn’t, look at X-rays, draw up differential diagnoses and start planning what different procedures I might have to do.”

Her schedule is “highly variable” but involves writing reports, ordering and interpreting testing, didactics and attending meetings. “In a typical workday, I’ll have three to five autopsy procedures, and depending on the case, each takes one to three hours,” Dr. Reynolds relayed. “We work in teams of three to four people per room in each of the facility’s two suites. Each pathologist works alongside at least one technician, a photographer and nearby supervising attending pathologists.”

Thanks to the prevalence of true crime dramas, many people likely have an image of medical examiners like Dr. Reynolds working alone in a dark basement. “That is absolutely not true,” she corrected. “Everything we do is for the sake of the living.”

Twice a day, Dr. Reynolds and her colleagues gather for rounds with the chief and deputy chief medical examiners, as well as representatives from investigations, autopsy technicians, radiology technicians and office management. Cases are discussed, and it’s a time to collaborate and get feedback and guidance.

“This is the second largest county in the United States, so there’s a lot going on here,” she said. “I’ve been most surprised by how many cases end up being people who have died of natural causes. I usually focus on what the next steps are for that patient—following up on ancillary testing, drafting reports and ultimately contacting loved ones and providing them with answers.”

Dr. Benjamin Soriano, staff pathologist and fellowship director at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office since 2019, said that Dr. Reynolds handles all those difficult tasks with grace. “Dr. Reynolds is incredibly passionate about the field of forensic pathology, and it shows in the quality of her work,” he said. “Her attention to detail is exceptional and she has a deep determination to solve the unanswered questions surrounding her patients’ deaths. She has maintained a positive attitude and high level of enthusiasm for the profession while training at one of the busiest offices in the country, where we see physically, emotionally and intellectually challenging cases on a daily basis. I look forward to having her join us as a staff pathologist in July and I know she will make a valuable addition to our team.”

“It’s very satisfying when I put pieces together to find out what happened to someone, especially when that person died unexpectedly and I’m able to figure that out,” Dr. Reynolds added. “I was recently assigned a case where a young person was found unresponsive in their home by a family member. The patient had no health history, there were no foul play concerns and no illicit substances or alcohol in their system. I ran toxicology tests, and I was able to determine that the cause of death was diabetic ketoacidosis. The family had had no idea.”

Thirty-two-year-old Reynolds was always interested in science. The Sioux Falls native attended Lincoln High School and Augustana College (now Augustana University). “As a senior at Lincoln, I really enjoyed anatomy class. I knew then that I’d work in some capacity of health care. While I was at Augustana, I volunteered in the emergency room at Avera McKennan, restocking supplies, turning over rooms and running errands. It was a good introduction to health care.”

Her time at Augustana was also her introduction to becoming multilingual, as she speaks French, Spanish and German. Learning French was somewhat of a fluke, she said, as her first two choices for the mandated two semesters of a foreign language were Spanish and German, but those classes were the first to fill. “The French course had openings and so I took it. Luckily, it just clicked,” she said. “Learning French was challenging but I was so interested in learning and gaining proficiency.”

Dr. Reynolds even studied language in Paris on two occasions, completing a four-week and an eight-week certificate program from the Institut Catholique de Paris, in June 2011 and again in July 2013.

Later, she took Spanish courses to get a modern foreign language minor and has taught herself to speak German by corresponding with extended family who live in Germany and studying the grammar on her own. “Speaking other languages has really helped me connect with patients on a deeper level,” Dr. Reynolds said.

Attending the Sanford School of Medicine was an introduction to another life-shaping concept when pathology came to the forefront of Dr. Reynolds’ interests during her second year of medical school. She referenced Dr. Michael Koch, who she said was so enthusiastic about the field that it piqued her interest. In her third year, during the Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship, Reynolds observed her first autopsy in conjunction with Minnehaha County Coroner and forensic pathologist Dr. Kenneth Snell. That sealed the deal.

“It was so cool, it reminded me of surgery,” she explained. “You get to see what happens, what is wrong, but it’s more of an intellectual puzzle to figure out how and why this person died. I just thought it was the coolest thing ever.”

Dr. Snell remembers that Reynolds shadowed him multiple times and described her as “attentive, interested in the cases and very knowledgeable about human anatomy and basic forensic pathology concepts.”

After graduating medical school, she headed to the University of Chicago Medical Center for her residency in anatomic pathology, followed by a fellowship in pediatric and perinatal pathology at the McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University. She was also able to rotate with the Medical Examiner Office (L’Institut médico-légal) in Paris for a month during her residency. She’s been with Cook County since then.

Her intense work certainly beseeches some mental outlets, and fortunately, Reynolds’ interests have helped her find those and settle into a busy life in Chicago. An avid runner, Reynolds has set a goal for herself to complete a half marathon or marathon in every state in the United States. “Yes, I run obscenely long distances for fun,” she quipped. “I started running for relaxation when I was in medical school and residency. It helps me blow off steam.

“The idea of running in every state came to me in a moment of pandemic shutdown induced cabin fever in 2020, wherein I found myself signing up for a winter race in Arizona for January 2022, partly as an excuse to travel again and see some friends and partly as an act of hope and faith that we’d be able to do things like travel again safely,” she continued.

She’s also an enthusiastic musician, playing the saxophone in a Chicago community band called the Windy City Winds. “Since age 10, I’ve played sax in my schools’ bands through middle and high school, including South Dakota All-State Jazz Band in 2006, 2007 and 2008. At Augie, I played in the Augustana Band, Northlanders Jazz Band and saxophone quartet. During medical school I played in Augie’s College and Community Band as well.”

It seems the young pathologist has found a formula for an equilibrium that works, balancing her career passion with her creative passion and finding rewards in all aspects of it.

“In this career, you get to experience the whole spectrum of humanity and of human emotion,” Reynolds explained. “Even though my patients are deceased, they are still my patients. I want to provide them the highest level of care, an attentive autopsy and follow up on testing or other investigative measures. I make sure I dot all i’s and cross all the t’s. I want to figure out who that person was and document it all accurately.”